Video produced by Theresa Chong/MEDILL. Animation by Next Media Animation, produced from a script by Theresa Chong.

Cicadas on the East Coast have been living underground for the past 17 years. They are ready to emerge this summer to mate,

lay eggs and die. After their long subterranean life, they die after only 4-6 weeks once they surface.

BY THERESA CHONG

JUN 6, 2013

Now that soil temperatures are warmer, millions of 17-year cicadas on the East Coast will emerge from beneath the ground this summer to mate, lay eggs and die.

They stage their appearance at different times and locations across the country. The 17-year cicadas last emerged in Illinois in 2007 and will be back in 2024.

Theresa Chong/MEDILL

“A Meticulous Beauty” exhibit by Jennifer Angus incorporates eight different insect species, including cicadas, in this art installation.

Jim Louderman, a collections assistant at The Field Museum, recalled frying them at the museum to celebrate the emergence. They “had a nutty flavor,” he said.

“Cicada’s are just one of those really dynamic insects that you can’t help coming across or talking about anytime you’re in entomology,” said Karen Wilson, a living invertebrate specialist at the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum.

According to De Anna Beasley, a cicada expert from the University of South Carolina, researchers are still uncertain how cicada’s know when to surface.

“We’re still not clear on exactly how the cicadas are timing their emergence,” she said. “Some have suggested that cicadas count the seasonal cycles of the trees they parasitize to determine when to emerge. It’s not perfect. There are incidences of individuals in a brood emerging a year early or late.”

But for those who have never encountered these mystifying creatures before, they should not be confused with locusts. Beasley said locusts are part of the Orthoptera family, which usually has large hind limbs that help them jump.

On the other hand, cicadas are closely related to the Hemiptera insect family and do not have large hind legs. “They have piercing mouthparts that they use to pierce the stem or roots of their host plant to suck out fluids,” she said. Butterflies also consume fluids or mashed foods. “On the other hand, locusts have chewing mouthparts and are similar to crickets and grasshoppers.”

Also, in terms of damage, “a large swarm of locusts can potentially cause significant damage to plant life because they chew and feed on leaves. Adult cicadas on the other hand are more interested in mating than feeding and will not cause significant harm to plant life,” Beasley said.

While underground, cicadas are not hibernating – they are feeding on sap from tree roots. “Actually, it’s a great strategy if you think about it.” Wilson said. “There’s nothing really that’s going to be able to eat them underground. They’re much safer down there.”

Although they can hide underground for well over a decade, when they do surface to the top they are no longer immune from predators.

Animals, birds and humans are known to consume a cicada or two. Jenna Jadin and the University of Maryland developed a cookbook called, “CICADA-LICIOUS: Cooking and Enjoying Periodical Cicadas.” Recipes include “soft-shelled cicadas,” “cicada dumplings,” and “emergence cookies.” The latter is essentially a chocolate cookie with cicadas strategically placed so they appear to be emerging from mud.

As a graduate biology student studying insects in 2004, Jadin said she ate “dozens and dozens” of cicadas while developing the recipes. “As a foodie who likes adventurous eating, I thought putting together a cookbook would be a fun way to get the public involved in this natural phenomenon,” she said.

When you break it down, eating a cicada is similar to eating a lobster, crab or shrimp.

“Well, they are all arthropods, ie. have exoskeletons and open circulatory systems,” Jadin said. “They are cleaner than the organisms you name which are all bottom feeders and eat garbage and decaying matter. Cicadas eat xylem (tree fluids) and have a cleaner diet and therefore should be LESS disgusting to think about eating.”

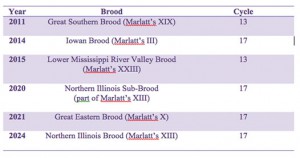

Chart produced by Theresa Chong/MEDILL. Chart information from the University of Illinois Extension, “Cicadas in Illinois”

http://web.extension.illinois.edu/cicadas/13or17year.html

Emergence schedule of cicadas.

Out of all of her recipes, Jadin’s favorite one is the chocolate covered cicadas. “First, the cicadas in that recipe are dried, which makes them tastier,” she said. “Second, anything tastes good covered in chocolate.”

Cicadas are usually found in tree branches making loud noises, otherwise known as the cicada “song,” which helps them find their mate. This also means that insect predators can more readily find them as well.

“You’ll hear the sound before you see the insect,” Wilson said. She remembered a time when she was tracking a cicada. “I was able to get very close to one, watch it moving its body and making that incredible sound. And as I watched, one of its main predators – the cicada killer wasp came swooping down and grabbed the actual insect I was looking at. Stung it, paralyzed it, flew off with it.”

But if you would rather be an observer rather than a predator, the Peggy Notebaert Nature Museum might be the place for you. At first glance, the “A Meticulous Beauty” exhibit by artist Jennifer Angus looks like colorful wallpaper.

But when your eye zooms in on the finer details of the installation, you see that the flower patterns are comprised of eight different types of insects from around the world. These include blue cicadas from Thailand, empress cicadas from Malaysia, and purple wing grasshoppers from French Guiana. It took five helpers and over three days to install thousands of unique insects on the wall.

“I hope that people will ask bigger questions than: “Are these real?” Angus said. “There are lots of insects that are on the endangered species list. They’re there because of loss of habitat primarily, not over collection. And, so for those who may feel upset, I think that’s a great reaction.”

Although the 17-year cicada is not endangered, according to Beasley it is difficult for scientists to predict the exact number of cicadas that will emerge – due to temperature and habitat. Since cicadas rely on trees for their life cycle, “areas that have experienced heavy urbanization or deforestation may have a significantly reduced emergence,” she said.

The emerging cicadas might inconvenience some people this year, but meeting the 17-year cicada isn’t such a bad thing after all.

“They’ll only be around for 4-6 weeks and it’s a rare and cool event to see (and hear!),” Beasley said. “We won’t see this brood again until 2030!”